Lambda Architecture

This article is Part 6 of 7 in the Intro to Data Streaming series:

- Part 1 - The Problem with Batch ETL - Part 1

- Part 2 - The Problem with Batch ETL - Part 2

- Part 3 - Data Streaming Learning Resources

- Part 4 - A Simple Real-Time App

- Part 5 - Improving the Real-Time App

- Part 6 - This Article

- Part 7 - Kappa Architecture

In the last part of the series we (nearly) completed the design of a conceptual real-time data streaming application, but were left with two remaining issues: shrinking batch windows and processing inefficiency. In large part the IT community has settled upon the solution: fault-tolerant compute clusters and distributed file systems, lead primarily by the Hadoop ecosystem and popular NoSQL data stores like MongoDB. We can mitigate the two primary challenges faced when working with shrinking batch windows, processing failures and data size, by scaling processing across multiple computers and building in (some types of) fault-tolerance to the system. As our batch windows shrink and data size grows the simplest and (often) most cost effective solution is to add commodity hardware to a compute cluster. However, these systems come with significant complexity. It is in this context that the Lambda Architecture was conceived.

The Lambda1 Architecture was defined in a 2011 blog post by Nathan Marz and further detailed in his book, Big Data. The (perhaps regrettable) title of his post, How to Beat the CAP Theorem, shows that he was concerned with the fundamental tradeoffs of distributed systems: consistency, availability, and partition tolerance (which you cannot sacrifice). In other words, while this series approaches the subject from the perspective of the batch ETL developer, Marz was attempting to overcome problems with the real-time processing systems circa 2011. A lot has been discussed about the CAP Theorem, much of which exposed the misconceptions and limited usefulness of the theorem as defined (see Problems with CAP, and Yahoo’s little known NoSQL system by Daniel Abadi (T) and especially Please stop calling databases CP or AP by Martin Kleppmann (T) ). Nevertheless, it remains a useful, if not sufficient, way to reason about distributed systems. Marz was wrestling with an essential question: given the reality of unreliable technological and human systems, how can we meet the potentially competing requirements of producing consistent and accurate data processing results in real-time?

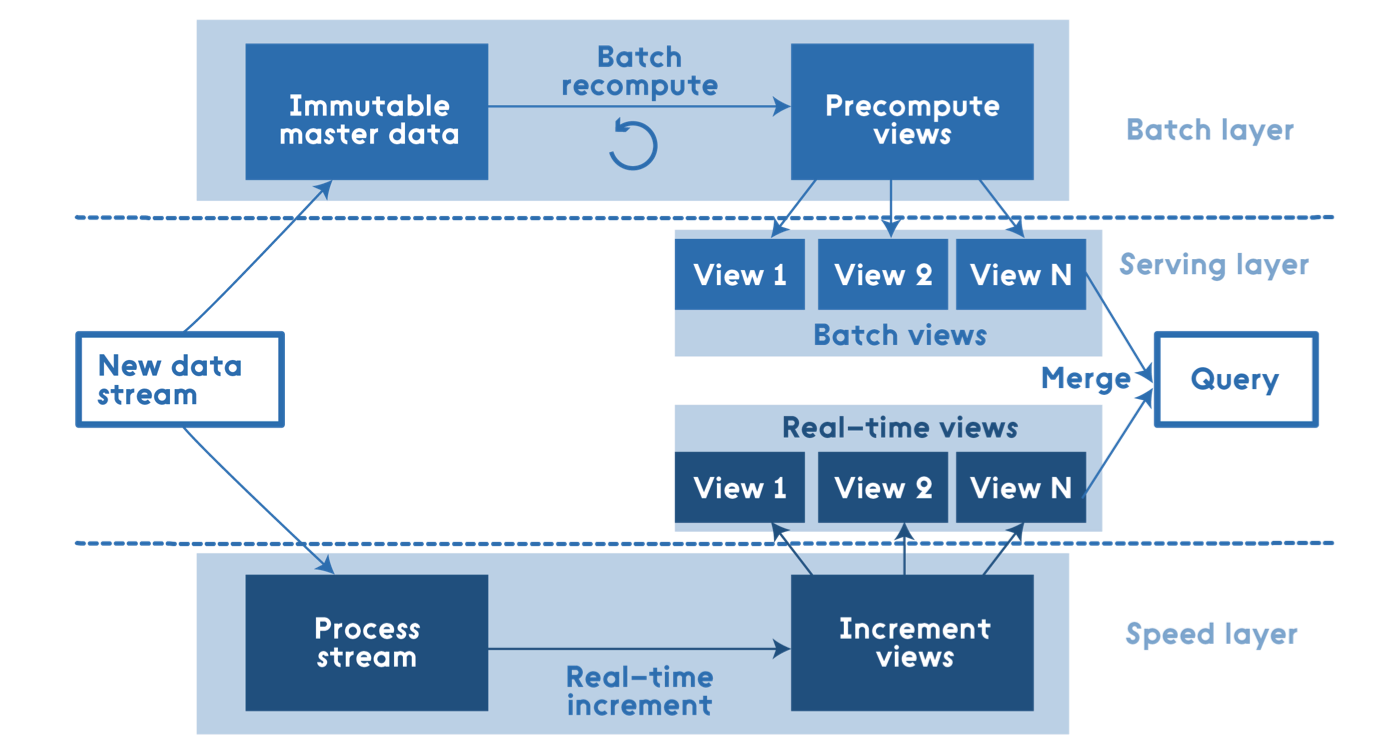

Marz described an architecture of ‘layers’, the ‘speed layer,’ ‘batch layer,’ and ‘serving layer,’ as shown in the following figure:

The batch layer is composed, as you would expect, of a distributed file system such as HDFS and a computation engine like Spark. In order to achieve real-time capabilities, however, another set of systems must be included. A low-latency distributed data store and a built-for-purpose real-time computation engine such as the Marz-authored Apache Storm, which is a popular option, are also required.

The concept is this: the batch layer provides the foundation of the architecture by producing provably-accurate results at a point-in-time at scale. In the time between execution of batch processing, the ‘speed layer’ is to consume data as it arrives and provide approximate calculations. These calculations may suffer from inaccuracies common to real-time processing, such as those caused by out-of-order messages, mistakes in code, or changing business requirements. But, not to worry, these temporary inaccuracies are corrected by the batch layer the next time processing occurs. Upon completion of batch processing, accumulated data that is not required for stateful real-time computation is purged from the speed layer, which minimizes resource utilization and latency. Thus, the ‘speed layer’ exists simply to bridge the timeliness gap between batch processing windows. Batch and real-time functions produce separate materialized views of the data that must be unioned at the ‘serving layer.’ The ‘serving layer’ is responsible for ensuring that the results produced by the two computation layers are reconciled and presented in a semantically consistent manner.

For Marz, batch processing presents a solution to the problems of real-time distributed data processing. At least in the presence of a system like Hadoop, it is as scalable. Most importantly, it is as simple data processing gets. Apply logic to a set of unchanging data and receive (eventually) accurate results. In his context wherein traditional batch processing problems have been solved through modifications to the overall architecture as described in parts 4 and 5 of this series Marz is correct that the primary problem with batch processing is that it does not produce results in real-time.

The Lambda Architecture has been implemented with success many times. And this is, needless to say, only a very high level overview appropriate for an introduction. I strongly urge you to read the blog post at a minimum, or even the book. It is, however, not without flaws. In the next part of the series we will examine these flaws in context of one proposed alternative, the Kappa Architecture.

- The term Lambda, refers to the computer science concept of anonymous functions that emerges from Lambda calculus. In this context, the fundamental principle of the architecture is to apply arbitrary functions to the data regardless of the layer of processing operations.