Kappa Architecture

This article is Part 7 of 7 in the Intro to Data Streaming series:

- Part 1 - The Problem with Batch ETL - Part 1

- Part 2 - The Problem with Batch ETL - Part 2

- Part 3 - Data Streaming Learning Resources

- Part 4 - A Simple Real-Time App

- Part 5 - Improving the Real-Time App

- Part 6 - Lambda Architecture

- Part 7 - This Article

The previous post in this series covered the Lambda Architecture, which conceives of a solution with three layers: the batch layer, the speed layer, and the serving layer. Implemented successfully many times, the Lambda Architecture provides a complete solution that ensures (eventual) accuracy of processing as well as real-time processing results. However, this achievement does not come without costs.

Jay Kreps outlined these costs in an influential blog post. In Questioning the Lambda Architecture, Kreps agrees with the basic propositions of the Lambda architecture, namely:

- Data consistency and accuracy are problems inherent in real-time distributed systems.

- Batch processing, in the context of modern architectural patterns and techniques, is an effective way of overcoming the limitations of real-time distributed systems.

However, Kreps focused on the Lambda Architecture’s weakness: complexity. While it is great, Kreps argues, that the Lambda Architecture can maintain conceptual consistency through implementing the same algorithms across its layers, the fact is that they are incongruent implementations. Each processing layer requires it’s own set of technologies and code bases that must be supported and maintained independently. And the serving layer is tasked with the potentially difficult challenge of reconciling results that may be overlapping or otherwise divergent. While clearly achievable, the Lambda Architecture is not as simple as it could be.

The problem, Kreps proposed, is not so much conceptual as technical. The Lambda principle that a data system is simply an assortment of functions applied to data is fundamentally correct, useful, and illuminating. However, the technological challenges of applying functions to small windows of data (real-time streams) are different than the problems of applying the same functions to all data at once. For real-time streams the primary concern is processing latency and is, therefore, typically network and CPU bound. For batch the primary concern is throughput, trying to optimize for the sheer volume of data being processed. It is typically disk I/O bound. Perhaps the reason why Marz had two processing layers in the Lambda Architecture is not because it is inherently required, but because no technological capability existed circa 2011 that serve both the requirements of real-time layer and the batch layer. For Kreps, the key remains his observation that the unifying data abstraction is the immutable transaction log. Having a persistent, ordered, log of all events that occur in your environment enables both real-time and batch processes.

Therefore, central to the architecture is Kreps’ most famous project, Apache Kafka. Kafka, he argued, checks all of the boxes required for the Lambda Architecture. By providing low-latency, distributed, event topics it can allow rapid access to events as they occur for real-time processing in a pub/sub pattern. By persisting these events in an ordered immutable log data structure that can be replayed at high-throughput, it can also serve batch needs. Following the Lambda principle, whereas a real-time algorithm is one that is applied to a ‘window’ of a single event, a batch algorithm is one that is applied to the entire log of events in total. In Kafka, this simply means you can implement batch processing simply by executing the same real-time code starting from the beginning of the log.

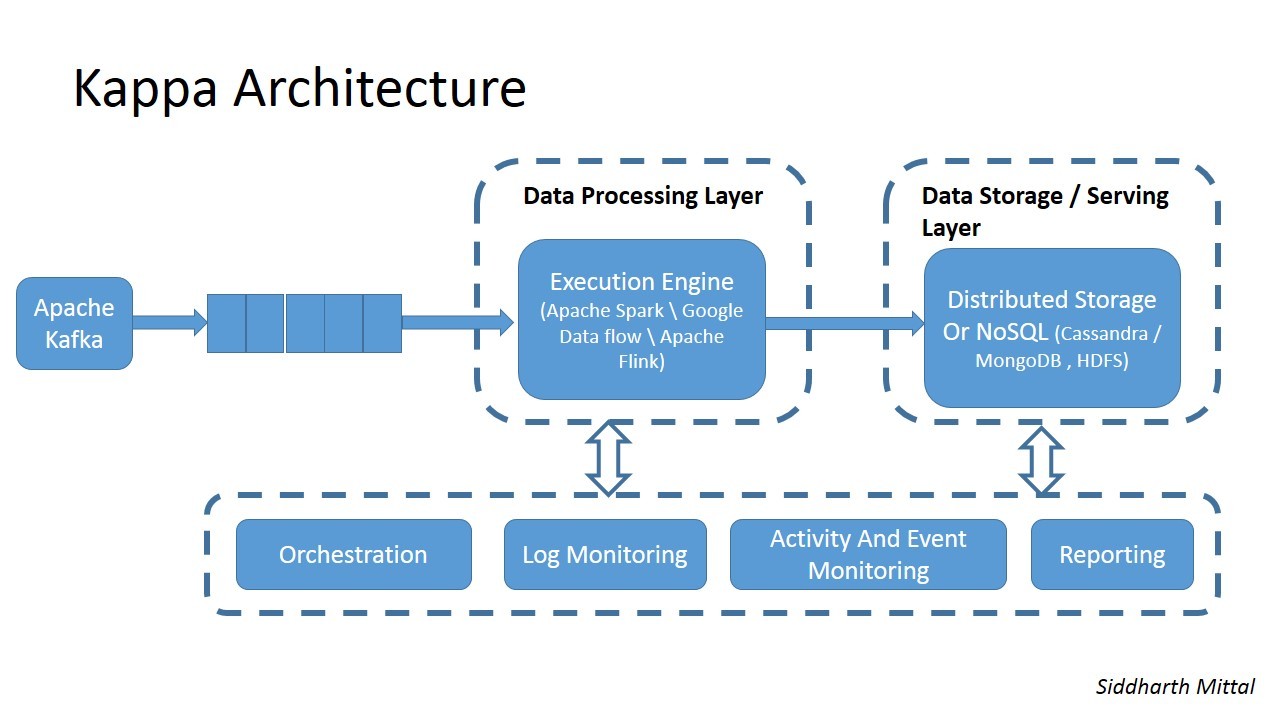

Kreps proposed a modification that looks something like this:

By adding Kafka as the central point of the architecture, the three conceptual layers of the Lambda Architecture can be merged into two. Inserting the immutable transaction log also serves the broader concerns of application integration. Readers of this series will observe that this is similar to the solution proposed in the 5th part of this series.

Note that the distributed immutable event log data structure and related semantics are gaining traction. Kafka is widely recognized as a critical component of many modern solutions, particularly in a micro-service architecture. Microsoft recently jumped into the fray adding a Kafka API to its Azure Event Hubs service. AWS Kinesis has enabled similar capabilities since late 2013.

Near the end of his post Kreps quibbled over the idea of naming his architecture. In my view he was right to do so as the Kappa architecture validates the fundamental concept of the Lambda Architecture. Pointing out that the same approach can be achieved with less complexity by utilizing a new type of platform may not justify a new name. Perhaps it would be better to have suggested Lambda 2.0. Regardless, it remains in the lexicon of distributed data systems.